I know we just went through the labor market where we discussed the factors affecting labor supply. The main factors were the birth rates, baby boomer generation, woman entering the labor force, and retirement age. I didn't go into a lot of detail about immigration. This is primary because illegal immigrant do not affect the labor supply in the United States. They are taking jobs American do not want to work. This is evident by the United Farm Workers campaign, "Take Our Jobs". They have opened up 700,000 jobs current occupied by immigrants. Only 16 people have applied for these positions (including Stephen Colbert). Here is nice piece by Ezra Klein.

So how can more immigration increase the wages of low skilled American workers?

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Monday, September 27, 2010

Are Sweatshops Good?

In the 2:10 section when talking about low skilled workers we got sidetracked talking about sweatshops where I made the comment sweatshops are good. Going in, I know this view is not in the majority, but at a minimum I ask that everyone keep an open mind. I know a number of students are passionate about this issue, as am I, so please be civil.

When I think about sweatshops this article (and these here and here and here) come to mind. Are sweatshops good? No. When comparing the alternatives for people living in poverty sweatshops do offer one avenue for hope and in that scope they are good. We've seen millions of people come out of poverty because of sweatshops not despite of.

Now can we have less human trafficking while paying above market wages to manufacturing workers in developing countries? I don't know. So far the evidence suggests not. Would I like to see firms pay these workers higher wages? Yes, but the reality of our economic model (i.e. capitalism) places large constraints on firms that will likely prevent this from happening. Corporations face tremendous pressure to maintain high levels of profit. We bet on these firms to keep increasing profits which comes at an unfortunate cost. As long as society demands high returns and/or low prices we will continue to have sweatshops. The global recession will only increase this pressure. This does not mean countries can't outgrow the need for sweatshops. Export led growth has been hugely beneficial for many Asian and Latin American economies (Brazil, China, Singapore, Philippines, Indonesia, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and many others). We've seen a number of economies grow from the stages of sweatshops into economic powers (including the United States). Sweatshops may not be necessary but so far they've proven to be sufficient. I'm not sure I want to experiment with an alternative model that may lead to more children being sold into the sex trade.

As a country we can do something. We can stop subsidizing agricultural production which will help restore jobs in many developing countries. The United States is responsible for destroying the lives of many farmers. Farm subsidies in the United States have created an excess supply of many agricultural commodities that we have dumped on the world market. This excess supply has created artificially low prices and forced a number of farmers off their land into manufacturing jobs (or into the U.S. as illegal immigrants). By removing farm subsidies a number of workers could leave factory life, return to farming, and wages will increase for those in the manufacturing sectors. This will help prevent the food shortages experienced across many developing nations. Here's another piece by Kristof.

Here are some good books on these issues:

Half the Sky by Kristof

In Defense of Globalization by Bhagwati

Making Globalization Work by Stiglitz

I love a few of his quotes:

When I think about sweatshops this article (and these here and here and here) come to mind. Are sweatshops good? No. When comparing the alternatives for people living in poverty sweatshops do offer one avenue for hope and in that scope they are good. We've seen millions of people come out of poverty because of sweatshops not despite of.

My point is that bad as sweatshops are, the alternatives are worse. They are more dangerous, lower-paying and more degrading. And when I struggle to think how we can really make a big difference in the development of the poorest countries, the key always seems to be manufacturing. (Kristof)Impoverished families need to find sources of income, if we force firms into paying higher than market wages (multinational companies already pay 2-3 times the wages of domestic manufacturing firms) fewer workers will be hired (law of demand). This will leave a number of people unemployed, they will be forced to find alternative sources of income. This is where the real exploitation begins. Families will sell children into the sex trade. There is a growing problem with human trafficking, the solution lies in more manufacturing firms not less. If this means more sweatshops, then yes please give me more sweatshops. Here's Paul Krugman's take.

Workers in those shirt and sneaker factories are, inevitably, paid very little and expected to endure terrible working conditions. I say "inevitably" because their employers are not in business for their (or their workers') health; they pay as little as possible, and that minimum is determined by the other opportunities available to workers. And these are still extremely poor countries, where living on a garbage heap is attractive compared with the alternatives.Pressuring firms into paying higher wages will simply result in the firms leaving the least developed countries for middle income countries that offer the opportunity to shift production for low skill labor to machines. What happens to the workers in the least developed countries?

Now can we have less human trafficking while paying above market wages to manufacturing workers in developing countries? I don't know. So far the evidence suggests not. Would I like to see firms pay these workers higher wages? Yes, but the reality of our economic model (i.e. capitalism) places large constraints on firms that will likely prevent this from happening. Corporations face tremendous pressure to maintain high levels of profit. We bet on these firms to keep increasing profits which comes at an unfortunate cost. As long as society demands high returns and/or low prices we will continue to have sweatshops. The global recession will only increase this pressure. This does not mean countries can't outgrow the need for sweatshops. Export led growth has been hugely beneficial for many Asian and Latin American economies (Brazil, China, Singapore, Philippines, Indonesia, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and many others). We've seen a number of economies grow from the stages of sweatshops into economic powers (including the United States). Sweatshops may not be necessary but so far they've proven to be sufficient. I'm not sure I want to experiment with an alternative model that may lead to more children being sold into the sex trade.

As a country we can do something. We can stop subsidizing agricultural production which will help restore jobs in many developing countries. The United States is responsible for destroying the lives of many farmers. Farm subsidies in the United States have created an excess supply of many agricultural commodities that we have dumped on the world market. This excess supply has created artificially low prices and forced a number of farmers off their land into manufacturing jobs (or into the U.S. as illegal immigrants). By removing farm subsidies a number of workers could leave factory life, return to farming, and wages will increase for those in the manufacturing sectors. This will help prevent the food shortages experienced across many developing nations. Here's another piece by Kristof.

Here are some good books on these issues:

Half the Sky by Kristof

In Defense of Globalization by Bhagwati

Making Globalization Work by Stiglitz

I love a few of his quotes:

As the nation-state developed, individuals felt connected to others within the nation—not as closely as to those in their own local community, but far more closely than to those outside the nation-state. The problem is that, as globalization has proceeded, loyalties have changed little. War shows these differences in attitude most dramatically: Americans keep accurate count of the number of U.S. soldiers lost, but when estimates of Iraqi deaths, up to fifty times as high, were released, it hardly caused a stir. Torture of Americans would have generated outrage; torture by Americans seemed mainly to concern those in the antiwar movement; it was even defended by many as necessary to protect the United States. These asymmetries have their parallel in the economic sphere. Americans bemoan the loss of jobs at home, and do not celebrate a larger gain in jobs by those who are far poorer abroad.

Most of us will always live locally—in our own communities, states, countries. But globalization has meant that we are, at the same time, part of a global community.

Tit for Tat

And so it begins, China responds to US pressure by increasing tariffs on imported poultry.

It appears to be a retaliatory move.

UPDATE: Going back to the initial reaction to the tire tariffs, Brad Delong calculated the cost of the tariffs.

It appears to be a retaliatory move.

UPDATE: Going back to the initial reaction to the tire tariffs, Brad Delong calculated the cost of the tariffs.

Friday, September 24, 2010

Colbert on Immigration

For those that like Stephen Colbert here is a video of him testifying in front of Congress on immigration reform. If you don't like him, it's still pretty funny.

Today we will start looking more closely at labor markets, including labor supply factors.

Today we will start looking more closely at labor markets, including labor supply factors.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

More Trade not Less

William Easterly argues more trade, not less, is needed to help the poor. I completely agree, instead of increasing trade barriers we need to reduce them. As the U.S. passes more protectionists policies it's only a matter of time before other countries follow suit.

Productivity and Real Wages

Here is a timely post on the comparison between worker productivity and real wages. We will beginning discussing the labor market (chapter 6) tomorrow.

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Why a little inflation might be good

Given we are currently talking about inflation I thought this article in the New Yorker might be relevant.

Why inflation might be good, two reasons. First, it helps reduce the real value of household and government debt. As you know, we have a lot of debt. Second, it creates an incentive to spend on goods today.

Why inflation might be good, two reasons. First, it helps reduce the real value of household and government debt. As you know, we have a lot of debt. Second, it creates an incentive to spend on goods today.

Monday, September 20, 2010

Homework 2

Here are the commonly missed problems:

43% got this problem correct:

Given the following data for an economy, compute the value of GDP.

60% got this problem correct:

Which of the following is NOT a capital good?

43% got this problem correct:

Given the following data for an economy, compute the value of GDP.

| 2,400 | |

| → | 2,500 |

| 2,600 | |

| 2,700 |

60% got this problem correct:

Which of the following is NOT a capital good?

| → | Batteries purchased by a car manufacturer to install in new cars |

| Machines purchased by a car manufacturer to measure metal thicknesses | |

| A new house purchased by a family | |

| A new apartment building purchased by a corporation |

Krugman on the causes of the financial crisis.

Paul Krugman and Robin Wells have a good review of the causes of the financial crisis. I am firmly in the group that believes the "global saving glut" played a large role in our financial crisis.

The Global Savings Glut

The term “global savings glut” actually comes from a speech given by Ben Bernanke in early 2005.1 In that speech the future Fed chairman argued that the large US trade deficit—and large deficits in other nations, such as Britain and Spain—didn’t reflect a change in those nations’ behavior as much as a change in the behavior of surplus nations. Historically, developing countries have run trade deficits with advanced countries as they buy machinery and other capital goods in order to raise their level of economic development. In the wake of the financial crisis that struck Asia in 1997–1998, this usual practice was turned on its head: developing economies in Asia and the Middle East ran large trade surpluses with advanced countries in order to accumulate large hoards of foreign assets as insurance against another financial crisis.

Germany also contributed to this global imbalance by running large trade surpluses with the rest of Europe in order to finance reunification and its rapidly aging population. In China, whose trade surplus accounts for most of the US trade deficit, the desire to protect against a possible financial crisis has morphed into a policy in which the currency is kept undervalued, which benefits politically connected export industries, often at the expense of the general working population.

For the trade deficit countries like the United States, Spain, and Britain, the flip side of the trade imbalance is large inflows of capital as countries with surpluses bought vast quantities of American, Spanish, and British bonds and other assets. These capital inflows also drove down interest rates—not the short-term rates set by central bank policy, but longer-term rates, which are the ones that matter for spending and for housing prices and are set by the bond markets. In both the United States and the European nations, long-term interest rates fell dramatically after 2000, and remained low even as the Federal Reserve began raising its short-term policy rate. At the time, Alan Greenspan called this divergence the bond market “conundrum,” but it’s perfectly comprehensible given the international forces at work. And it’s worth noting that while, as we’ve said, the European Central Bank wasn’t nearly as aggressive as the Fed about cutting short-term rates, long-term rates fell as much or more in Spain and Ireland as in the United States—a fact that further undercuts the idea that excessively loose monetary policy caused the housing bubble.

Indeed, in that 2005 speech Bernanke recognized that the impact of the savings glut was falling mainly on housing:

During the past few years, the key asset-price effects of the global saving glut appear to have occurred in the market for residential investment, as low mortgage rates have supported record levels of home construction and strong gains in housing prices.What he unfortunately failed to realize was that home prices were rising much more than they should have, even given low mortgage rates. In late 2005, just a few months before the US housing bubble began to pop, he declared—implicitly rejecting the arguments of a number of prominent Cassandras2:—that housing prices “largely reflect strong economic fundamentals.”3 And like almost everyone else, Bernanke failed to realize that financial institutions and families alike were taking on risks they didn’t understand, because they took it for granted that housing prices would never fall.

Despite Bernanke’s notable lack of prescience about the coming crisis, however, the global glut story provides one of the best explanations of how so many nations managed to get into such similar trouble.

The Economists' take on our future debt

Here's a good article discussing the consequences of Americans shifting into more saving and reducing household debt. I've mentioned before, the result will be slower economic growth over the next decade, but this will put us in a better financial position to address social security and health care. We need to create more incentives for households to save, one example could be a switch from an income tax to a spending tax (or a value added tax). Right now we are taxing any income that is not spent buying a home, paying for college, given to charity, or saved in retirement plan. We are not encouraging households to save money. We need to allow households to save money in relatively liquid accounts without paying income taxes. This saving will further reduce our dependency on foreign investment.

Has the crisis changed the teaching of economics?

Here is a discussion on the Economist about teaching economics and the crisis. A lot of the discussion is focused on upper/graduate courses, but the reading list proposed by Michael Bordo is particular interesting. At Oregon I required all my students in my money and banking course to read, "Manias, Panics, and Crashes" by Charles Kindleberger. At Gonzaga I teach an course entitle "Economics of Financial Crises". The two books that I have required students to read are "This Time is Different. Eight Centuries of Financial Folly" by Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff and "Manias, Panics, and Crashes." For anyone wanting to better understand the crisis start here. In my intermediate macroeconomics course next spring "The Time is Different" will be required reading.

Apparently I want to extend the tax cuts

Here is a survey posted on CNN that shows 60% of economists want Bush's tax cuts extended for all income levels. This isn't far from what I've suggested. There are two forces at work: the recession and government debt. In the short run we need the economy to recover, but we can't afford to keep the tax cuts permanent. Let's extend the tax cuts for all income levels and then starting in 2013 slowly phase in tax increases for the upper groups. To help offset the tax cuts we need to find spending cuts, but again lets not implement those until 2015 or later if the economy is still slow.

Friday, September 17, 2010

It's good to be a college student (or grad or professor)

Here's an interesting piece from the NY Times. Enjoy college while it lasts, or be like me and never leave.

Inflation or Deflation

Does it seem like prices have been increasing over the last year. Well the have been, but we're not going to call it inflation. Recent inflation data show prices have increased at annualized rate of 1.1%. This is a fairly low number and could further push the economy into decline. Despite modest inflation in what we call the core CPI overall prices rose 4.4%. This number includes energy and food prices. We normally strip away these food and energy because they are highly volatile and don't paint an accurate picture of prices. In the last few years we had oil prices spike due to speculative trading, this summer wheat prices have spiked due to the first in Russia, and other commodities (coffee for example) are rising in response.

The Federal Reserve does not worry about rising energy and food prices simply because these are outside of their control.

The Federal Reserve does not worry about rising energy and food prices simply because these are outside of their control.

Thursday, September 16, 2010

China is now focused on the Yen

China has increased their purchases of Japanese yen. This action will cause the yen to appreciate and the yuan to depreciate. China's goods will be less expensive relative to Japans'.This is important for a couple of reasons. First China must see increased competition from Japanese exports. Second they are moving away from dollar dominated assets. The latter could prove costly for the United States. Right now we are heavily dependent of foreign purchases of US debt. If China is committing to Japan's debt this could cause a depreciation in the dollar. As investors expect the dollar to decline they will demand greater interest rates. In the end, this could greater increase the cost of running large government deficits.

Wednesday, September 15, 2010

Quiz 1

Most students lost points on numbers 2 and 3. Here are some thoughts I had while grading the quizzes.

#1 Identify the flaw in this analysis: ”If more Americans go on a low-carb diet, the demand for bread will fall. The decrease in the demand for bread will cause the price of bread to fall. The lower the price, however, will then increase the demand. In the new equilibrium, Americans might end up consuming more bread than they did initially.”

A lot of people are going around and around with this problem. Demand decreases because of people's preferences. The result is a new equilibrium where price and quantity have declined. The lower price is the result of a change in one of the determinants of demand (preferences). End of story. A lower price does not in turn increase demand.

A common mistake is to assume those not on the low-carb diet will increase their consumption and demand will increase. At the original equilibrium, stores will realize fewer people buying bread. A surplus will emerge. Stores/bakeries must lower prices to sell the excess bread.

#2 Consider the following events: Scientists reveal that consumption of oranges decreases the risk of diabetes and, at the same time, farmers use a new fertilizer that makes orange trees more productive. Illustrate and explain what effect these changes have on the equilibrium price and quantity of oranges.

(This problem is similar to the last five problems in the practice set supply and demand)

Demand will shift to the right (increase) causing price and quantity to increase. Supply will shift to the right (increase) causing price to decrease and quantity to increase. In the end we know quantity will increase but the effect on price is indeterminate.

Common mistakes were saying price stayed the same or having a definitive answer. There were a handful of answers that incorrectly shifted supply (an increase is a rightward/downward shift). Finally, a few people forgot to illustrate the effects.

#3 Residents of your city are charged a fixed weekly fee of $6 for garbage collection. They are allowed to put out as many cans as they wish. The average household disposes of three cans of garbage per week under this plan. Now suppose that your city changes to a tag system. Each can of garbage to be collected must have a tag affixed to it. The tags cost $2 each and are not reusable. What effect do you think the introduction of

the tag system will have on the total quantity of garbage collected in your city?

(This problem is similar to our discussion on overeating at all-you-can-eat buffets. Also see the practice set on the introductory material).

In the first case, the cost is $6 per week no matter how many cans you put out, so the cost of disposing of an extra can of garbage is $0. Under the tag system, the cost of putting out an extra can is $2, regardless of the number of the cans. Since the marginal cost of putting out cans is higher under the tag system, we would expect this system to reduce the number of cans collected.

You need to have mentioned marginal cost in your answer or have some reference to it. Most students discussed that on average the quantity won't change because those that original consumed more than 3 cans would decrease their waste while those that consumed less than 3 cans would increase their waste. The key to getting credit for this problem is recognizing the price per can has increased from $0 to $2.

#4 What’s the best way to think about the rise in oil prices in the last 10 years, as China and India have become richer: was it a rise in demand, a fall in demand, a rise in supply, or a fall in supply? Why?

China and India represent more buyers in the market. As the number of buyers increase demand will shift to the right, causing quantity and price to increase.

A lot of people fell into the trap that as China and India increased their demand for oil, the supply must have fallen. My guess is you're thinking of oil being in fixed supply, but you need to think about the market. Was less oil supplied to the market? No, their might be less oil in the ground, but this doesn't mean supply fell.

#1 Identify the flaw in this analysis: ”If more Americans go on a low-carb diet, the demand for bread will fall. The decrease in the demand for bread will cause the price of bread to fall. The lower the price, however, will then increase the demand. In the new equilibrium, Americans might end up consuming more bread than they did initially.”

A lot of people are going around and around with this problem. Demand decreases because of people's preferences. The result is a new equilibrium where price and quantity have declined. The lower price is the result of a change in one of the determinants of demand (preferences). End of story. A lower price does not in turn increase demand.

A common mistake is to assume those not on the low-carb diet will increase their consumption and demand will increase. At the original equilibrium, stores will realize fewer people buying bread. A surplus will emerge. Stores/bakeries must lower prices to sell the excess bread.

#2 Consider the following events: Scientists reveal that consumption of oranges decreases the risk of diabetes and, at the same time, farmers use a new fertilizer that makes orange trees more productive. Illustrate and explain what effect these changes have on the equilibrium price and quantity of oranges.

(This problem is similar to the last five problems in the practice set supply and demand)

Demand will shift to the right (increase) causing price and quantity to increase. Supply will shift to the right (increase) causing price to decrease and quantity to increase. In the end we know quantity will increase but the effect on price is indeterminate.

Common mistakes were saying price stayed the same or having a definitive answer. There were a handful of answers that incorrectly shifted supply (an increase is a rightward/downward shift). Finally, a few people forgot to illustrate the effects.

#3 Residents of your city are charged a fixed weekly fee of $6 for garbage collection. They are allowed to put out as many cans as they wish. The average household disposes of three cans of garbage per week under this plan. Now suppose that your city changes to a tag system. Each can of garbage to be collected must have a tag affixed to it. The tags cost $2 each and are not reusable. What effect do you think the introduction of

the tag system will have on the total quantity of garbage collected in your city?

(This problem is similar to our discussion on overeating at all-you-can-eat buffets. Also see the practice set on the introductory material).

In the first case, the cost is $6 per week no matter how many cans you put out, so the cost of disposing of an extra can of garbage is $0. Under the tag system, the cost of putting out an extra can is $2, regardless of the number of the cans. Since the marginal cost of putting out cans is higher under the tag system, we would expect this system to reduce the number of cans collected.

You need to have mentioned marginal cost in your answer or have some reference to it. Most students discussed that on average the quantity won't change because those that original consumed more than 3 cans would decrease their waste while those that consumed less than 3 cans would increase their waste. The key to getting credit for this problem is recognizing the price per can has increased from $0 to $2.

#4 What’s the best way to think about the rise in oil prices in the last 10 years, as China and India have become richer: was it a rise in demand, a fall in demand, a rise in supply, or a fall in supply? Why?

China and India represent more buyers in the market. As the number of buyers increase demand will shift to the right, causing quantity and price to increase.

A lot of people fell into the trap that as China and India increased their demand for oil, the supply must have fallen. My guess is you're thinking of oil being in fixed supply, but you need to think about the market. Was less oil supplied to the market? No, their might be less oil in the ground, but this doesn't mean supply fell.

Picture of the Week

Here's a chart breaking down what percent of small businesses cited each of these problems as their biggest challenge, going back to 1986

Three Stocks that Beat the Recession

We won't spend a lot of time on the stock market, but I thought the first two stocks were interesting. Anyone know why McDonalds and Campbell's Soup would increase during a recession (here's the link)? During the stock market panic of 2008, Campbell's Soup was the only company that did not experience a decrease in their value when the Dow Jones Index fell 777 points (the largest one day point loss).

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

Labor Force Participation

This post is about a week early, as next week we will begin talking about unemployment. Nonetheless, The Federal Reserve Bank San Francisco published a recent letter discussing the future of declining unemployment rates is conditional on the movement of workers back into the labor force. During the recession a number of workers left the labor force. These workers went back to school, became stay at home parents, etc. They are discouraged workers. As the economy improves nearly six million workers will have to decide whether they want to reenter the labor force. The speed at which these workers find jobs will dictate the future unemployment rate.

Sunday, September 12, 2010

Assignment #1

The average for the first homework assignment was 81.3%. Here are the three most missed problems:

#4 (35% correct) Larry was accepted at three different graduate schools, and must choose one. Elite U costs $50,000 per year and did not offer Larry any financial aid. Larry values attending Elite U at $60,000 per year. State College costs $30,000 per year, and offered Larry an annual $10,000 scholarship. Larry values attending State College at $40,000 per year. NoName U costs $20,000 per year, and offered Larry a full $20,000 annual scholarship. Larry values attending NoName at $15,000 per year.

The opportunity cost of attending Elite U is

The correct answer is $20,000. The question is asking for the opportunity cost of attending Elite U. Recall opportunity cost is the value of the next best alternative. In this case, Larry would receive a value of $20,000 by attending State U.

#6 (40% correct) Amy is thinking about going to the movies tonight. A ticket costs $7 and she will have to cancel her dog-sitting job that pays $30. The cost of seeing the movie is

The correct answer is $37. The question is asking for the cost, not the overall value. I suspect those that got the question wrong answers $37 minus the benefit of seeing the movie. If Amy starts the night with $10 and goes to work she will have $40. If she goes to the movie instead she's left with $3. The difference between the two options is $37.

#3 (58% correct) Dean decided to play golf rather than prepare for his exam in economics that is the day after tomorrow. One can infer that

The correct answer is the "economic surplus from playing golf exceeded the surplus from studying". I suspect most people answered "the cost of studying was less than the cost of golfing". Suppose the cost of studying was $0 and the cost of golfing was $10. Wouldn't you choose to study if you were basing you decision off of costs alone. The key in this question was Dean did golf which means he received at least more value (or surplus or warm fuzzy feelings) from golfing. This question is a lot like our classroom example where you had to decide between the two concerts. If you went to the Bruce Springsteen concert than you must have received more than $10 in surplus or you would have gone to the Bob Dylan concert.

#4 (35% correct) Larry was accepted at three different graduate schools, and must choose one. Elite U costs $50,000 per year and did not offer Larry any financial aid. Larry values attending Elite U at $60,000 per year. State College costs $30,000 per year, and offered Larry an annual $10,000 scholarship. Larry values attending State College at $40,000 per year. NoName U costs $20,000 per year, and offered Larry a full $20,000 annual scholarship. Larry values attending NoName at $15,000 per year.

The opportunity cost of attending Elite U is

| $50,000 | |||||||

| $10,000 | |||||||

| → | $20,000 | ||||||

| $15,000 |

#6 (40% correct) Amy is thinking about going to the movies tonight. A ticket costs $7 and she will have to cancel her dog-sitting job that pays $30. The cost of seeing the movie is

| $7. | |

| $30. | |

| → | $37. |

| $37 minus the benefit of seeing the movie. |

#3 (58% correct) Dean decided to play golf rather than prepare for his exam in economics that is the day after tomorrow. One can infer that

| Dean has made an irrational choice. | |

| Dean is doing poorly in his economics class. | |

| → | the economic surplus from playing golf exceeded the surplus from studying. |

| the cost of studying was less than the cost of golfing. |

Inflation in China

Inflation is rising in China. Why do we care about Chinese inflation?

As you probably realize the economies of China and the United States are more intertwined than ever. Over the last two decades China focused their domestic policies toward export lead growth. This was primarily achieved through a pegged exchange rate. The lower the value of the yuan the cheaper it was for Americans to covert dollars into yuan and buy more Chinese goods. Foreign investors began flocking for Chinese firms. As foreign money flowed into China normally the yuan would appreciate. An appreciation would make exports more expensive and slow down manufacturing in the export sectors. To offset the added demand China would increase their money supply and use the money to buy U.S. denominated assets. These policies allowed China to have a large trade surplus with the United States, conversely a large deficit for the United States.

There are costs to maintaining a pegged exchange rate. During the financial crisis the United States increased the money supply, i.e. lower interest rates, to stave off a financial panic. As more dollars enter the economy the value declines relative to foreign currencies. This would cause the yuan to appreciate unless the Chinese government undertook the same policies (by pegging the yuan to the dollar China is effectively adopting U.S. monetary policy). Here's the concern for China, their economy is starting to grow relative to the United States, but they cannot maintain their pegged exchange rate without risking double digit inflation rates. They are faced with an appreciation of the yuan or higher inflation both will increase the cost of Chinese goods on the global market. Unfortunately, I don't see this being overly beneficial to the United States. Our manufacturing does not complete directly with China, it won't immediately cause jobs to return to the U.S., and it will result in higher prices to households.

As you probably realize the economies of China and the United States are more intertwined than ever. Over the last two decades China focused their domestic policies toward export lead growth. This was primarily achieved through a pegged exchange rate. The lower the value of the yuan the cheaper it was for Americans to covert dollars into yuan and buy more Chinese goods. Foreign investors began flocking for Chinese firms. As foreign money flowed into China normally the yuan would appreciate. An appreciation would make exports more expensive and slow down manufacturing in the export sectors. To offset the added demand China would increase their money supply and use the money to buy U.S. denominated assets. These policies allowed China to have a large trade surplus with the United States, conversely a large deficit for the United States.

There are costs to maintaining a pegged exchange rate. During the financial crisis the United States increased the money supply, i.e. lower interest rates, to stave off a financial panic. As more dollars enter the economy the value declines relative to foreign currencies. This would cause the yuan to appreciate unless the Chinese government undertook the same policies (by pegging the yuan to the dollar China is effectively adopting U.S. monetary policy). Here's the concern for China, their economy is starting to grow relative to the United States, but they cannot maintain their pegged exchange rate without risking double digit inflation rates. They are faced with an appreciation of the yuan or higher inflation both will increase the cost of Chinese goods on the global market. Unfortunately, I don't see this being overly beneficial to the United States. Our manufacturing does not complete directly with China, it won't immediately cause jobs to return to the U.S., and it will result in higher prices to households.

Saturday, September 11, 2010

More on the Bush tax cuts

Jeffrey Mirron wrote a piece for the NY Times.

This claim is true in part; lower tax rates on the high income earners are obviously beneficial for those earners. Yet this is only part of the story. To stimulate work, saving, and investment, tax cuts have no choice but to favor the taxpayers who respond most to taxes, as well as those likely to save and invest. That means high income earners. So policy must accept some inequality in exchange for more efficiency.In theory this is true, but the reality is not nearly as neat as Mirron would like. The wealthy barely responded to the initial tax cut, will there by a lot of change if the tax rates on those making $250,000+ increase?

Warren Buffet has said repeatedly that he does not think it's fair that he pays a lower tax rate than his house cleaner. For those that earn income on investment (via capital gains) they pay an tax rate of 15%. This is lower than more pay on earned income. A lower capital gains tax allows for riskier behavior. One can not writing off the reduction in the capital gains taxes in 2003 as a potential cause of the housing bubble. All of the sudden those make speculative real estate purchases were paying less in taxes.

And in the case of dividend and capital gains taxation, the economy can have its cake and eat it too. These taxes appears to hit wealthy capitalists, but in reality they fall partly on consumers, via higher prices, and on workers, via lower demands for their services when corporations shut down or move overseas. So low taxation of dividends and capital gains helps both low and high income taxpayers.

Mirron is right on here. Obama needs to allow business to deduct the full amount of their investments permanent. A one year benefit will only create more uncertainty. I have address the uncertainty of a patchwork policy framework in a previous post. We need to end uncertainty over governmental policy. This could have been done two years ago when we passed ARRA. We should have addressed the tax cuts (my view is to extend the cuts for all tax payers and then in 1-2 years have a slow increase for the high income earners perhaps conditional on economic growth), to counter the impact on future deficits we can offset the tax cuts with reductions in spending (but not until 2015).

President Obama is opposed to extending the Bush tax cuts and is instead proposing to allow full write-off of business investment through 2011. This proposal is reasonable, but the impact is likely to be small; this policy merely allows businesses to deduct investment now rather than later as depreciation. Given currently low interest rates, this shifting of expenditure is not worth much.

A different problem with the president’s approach is that it emphasizes short-run stabilization, not long-run efficiency. To prosper over the long haul, the economy needs certainty about taxes, rules, and regulations, not ever-evolving policy initiatives.

Who Say's Rent Control is Inefficient.

Greg Mankiw found out about "A Dastardly Clever Scheme"

At a faculty lunch yesterday, I heard about an ingenious scheme used by some universities in New York, where much rental housing is rent controlled. Here are the three key elements, as it was described to me by one of my colleagues:

1. The university buys a rent-controlled building. The purchase price is low, because the existing landlord cannot make much money renting it.

2. The university then rents the apartments to its own senior faculty, who view this as a great perk. In essence, the difference between the free-market rent and the controlled rent is a form of compensation for the professor. As a result, the university can reduce the professor's cash compensation by an equivalent amount. The university is effectively earning the market rent for the apartment.

3. But it gets even better. The implicit rental subsidy is a form of non-taxed compensation. Normally, if an employer gives an employee a perk like this, the subsidy is taxable income (unless the perk is deemed a working condition required to do the job, like a hotel manager living in a hotel). But here, the university can claim there is no subsidy: It is only charging what the rent-control law requires. Because of this tax treatment, the implicit subsidy is worth even more to the professor than the equivalent cash compensation. This fact allows the university to reduce the professor's cash compensation by an even greater amount. Thus, the university effectively earns even more than the free-market rent on a real estate investment purchased much lower than the free-market price would have been.

In the end, the goal of the rent control laws is thwarted (the low rents are enjoyed by well-paid tenured faculty rather than the needy), the income tax laws are thwarted (a sizable part of compensation is untaxed), and all this is done by a nonprofit institution (the university) whose ostensible purpose is to serve the public interest.

Friday, September 10, 2010

Krugman on us and Japan

Paul Krugman has a good piece comparing our current economic situation with Japan.

Thursday, September 9, 2010

Trade Deficit Improves

Here's an article discussing the impact of a lower trade deficit and what it means for growth. How does trade affect economic growth. Gross domestic product (GDP) is the market value of all final goods produced in a given period within a country. There are a couple GDP accounting methods. We will primarily focus on the expenditure approaches. This methods sums up household consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports (exports less imports). Household consumption include durable and nondurable goods and inventories. Investment accounts for business investment in new equipment, inventories, and new purchases of homes. Net exports are simply correcting for where the goods are produced. As you can see an increase in net exports will increase GDP, but does a reduction in our trade deficit necessarily result in a higher measure of GDP? If the reduction in the trade deficit occurs because of increase in exports, than yes a lower trade deficit will increase economic growth (economic growth is the annual rate of change of GDP). But if the trade deficit is lower because we have imported less, unless households have switched from buying foreign into buying U.S. than a reduction in the trade deficit will not necessarily improve growth. Alright so what is it?

The Bureau of Economic Analysis is responsible for measuring GDP and we won't know the effect on consumption until next quarter. But we can gain some insight into looking at the past data here. What can we learn? If we look at quarter four in 2009 we can see a large gain in exports ($83 billion), a modest increase in imports ($20 billion), and another modest gain in consumption ($20 billion). As we can see an increase in exports was the primary reason for an increase in GDP. This table shows the contribution to GDP by each component in quarter four of 2009 the economy grew at a 5% rate, and nearly half of this was from more exports.

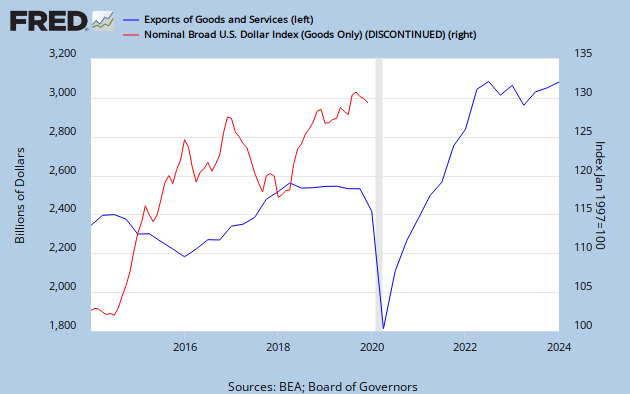

What caused the increase in exports? The increase in exports is likely a function of an incease in income abroad and a lower dollar exchange rate. As you can see a decline in the value of the dollar (red line) corresponds closely with an increase in exports (blue line). This is one benefit of the dollar depreciation.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis is responsible for measuring GDP and we won't know the effect on consumption until next quarter. But we can gain some insight into looking at the past data here. What can we learn? If we look at quarter four in 2009 we can see a large gain in exports ($83 billion), a modest increase in imports ($20 billion), and another modest gain in consumption ($20 billion). As we can see an increase in exports was the primary reason for an increase in GDP. This table shows the contribution to GDP by each component in quarter four of 2009 the economy grew at a 5% rate, and nearly half of this was from more exports.

What caused the increase in exports? The increase in exports is likely a function of an incease in income abroad and a lower dollar exchange rate. As you can see a decline in the value of the dollar (red line) corresponds closely with an increase in exports (blue line). This is one benefit of the dollar depreciation.

More on the fiscal stimulus

President Obama has proposed a $350 billion stimulus package. The package would jointly focus on infrastructure projects along with investment tax credits for firms. Both of these programs would provide well needed stimulus, but I high doubt a bill can get passed that is as simple as this. Earlier I said a $100 billion package would be too small and larger packages would likely not get passed. I do like how this bill focuses on upgrading the infrastructure in our country. Now why didn't the first stimulus bill do something similar? I am worried about this adding to our long-term government debt, but the longer we stay in a recession the lower tax revenues and higher government spending will continue.

Greg Mankiw does like the idea but argues we need more. Again, citing the need to convert household saving into investment.

Greg Mankiw does like the idea but argues we need more. Again, citing the need to convert household saving into investment.

Wednesday, September 8, 2010

Understanding Home Foreclosure

I remember reading this piece awhile back. It helps to understand how so many people fell victim to the housing bubble.

Monday, September 6, 2010

Is it time for more stimulus?

With the economy in a rut President Obama has started selling a second economic stimulus package. I have mixed emotions over another package (here is a good dialogue on the debate). When the economy hits a downturn the federal government feels complied to act. This action can be through added government spending, tax credits, or reductions in tax rates.

It is important to differentiate between tax credits and tax rates. Tax credits are one time payments to an individual or household, these included the first time home buyer credit, temporary exclusions to the alternative minimum tax, and lump sum checks handed out in the summer of 2008. Reduction in tax rates can include reductions in the personal income tax rate (like we had in 2001) and corporate income taxes. Few economists questioned the need for a stimulus package, but there was plenty of debate over the size and make up of the bill. Should the bill be $500 billion or $2 trillion? Should we target government spending or tax cuts? When the government decided it was time for a stimulus package, they passed the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act. The bill added over $800 billion in government spending and tax cuts which appeased some politicians but angered nearly every economist.

Economic research shows government spending on infrastructure and state aid (for unemployment) and reductions in the tax rates have the largest multiplier effect. Unfortunately, political pressure forced the bill to abandon nearly $400 billion earmarked for infrastructure projects and placed into one time tax cuts. We essentially took money out of programs that would have helped create jobs, passed them along to individuals who saved the money. In times of economic slowdowns added income is saved. Normally this is not all bad, added savings gets funneled into banks and in time loaned out. But because of large loan losses in real estate banks decided to hoard cash. Tax cuts had little economic impact. (The CBO confirms this in their quarterly updates of the ARRA)

A better bill would have done four things. First, a large portion of the stimulus should have gone to upgrading infrastructure (roads, bridges, hospitals, schools, energy grid, air traffic control) that is vital to economic growth. Further, these projects would have created jobs for those in the manufacturing and construction industry. Second, the government should have addressed the expiring Bush tax cuts. Although I think the tax cuts in 2001 were not very effective in helping the economy recover from the recession back then and further worsened our government debt letting them expire at the end of 2010 will greatly hamper any recovery we maybe experiencing. Third, the stimulus package should have provided ample aid to states. Again multiplier estimates show unemployment compensation has one of the largest stimulus effects. Finally the stimulus package would have included money to help struggling homeowners. There are a large number of homeowners who did things right and have jobs, but find themselves underwater in their mortgage. Imagine buying a $300,000 home and putting $30,000 or $60,000 down to find yourself living in a home worth $150,000. You did nothing wrong, the government wanted everyone to be a homeowner and live the American Dream. Why are we punishing individuals that are doing it the right way? The government needed to help these homeowners restructure their loans which would have provided badly need stability to housing prices. In the end this bill would have cost significantly more, probably in the $1.5-2 trillion dollar range (nearly half would be from the extension of the tax cuts), but we would address a lot of future uncertainty back in 2009. As it stands we are left doing a patchwork of bills that will likely cost more than $2 trillion.

(One thing I didn't address was the tax credits for developing alternative energies. I think a more direct approach would be to tax dirty energies directly and let the market develop sustainable alternative energies. I will talk about this more in a later post.)

Now the government is wanting to pass another bill. Although this bill sounds like it has some good intentions, it is hard to say what the bill will look like after it goes through the political process. Additionally, we have to ask ourselves if we can afford another bill. Right now the patchwork process is not helping anyone, adding another $100 billion in spending will likely have little to no economic impact in the short run. At the same time I don't think we can afford a $1 trillion package that is similar in make up to the ARRA. This really puts the economy and politicians at a crossroads.

It is important to differentiate between tax credits and tax rates. Tax credits are one time payments to an individual or household, these included the first time home buyer credit, temporary exclusions to the alternative minimum tax, and lump sum checks handed out in the summer of 2008. Reduction in tax rates can include reductions in the personal income tax rate (like we had in 2001) and corporate income taxes. Few economists questioned the need for a stimulus package, but there was plenty of debate over the size and make up of the bill. Should the bill be $500 billion or $2 trillion? Should we target government spending or tax cuts? When the government decided it was time for a stimulus package, they passed the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act. The bill added over $800 billion in government spending and tax cuts which appeased some politicians but angered nearly every economist.

Economic research shows government spending on infrastructure and state aid (for unemployment) and reductions in the tax rates have the largest multiplier effect. Unfortunately, political pressure forced the bill to abandon nearly $400 billion earmarked for infrastructure projects and placed into one time tax cuts. We essentially took money out of programs that would have helped create jobs, passed them along to individuals who saved the money. In times of economic slowdowns added income is saved. Normally this is not all bad, added savings gets funneled into banks and in time loaned out. But because of large loan losses in real estate banks decided to hoard cash. Tax cuts had little economic impact. (The CBO confirms this in their quarterly updates of the ARRA)

A better bill would have done four things. First, a large portion of the stimulus should have gone to upgrading infrastructure (roads, bridges, hospitals, schools, energy grid, air traffic control) that is vital to economic growth. Further, these projects would have created jobs for those in the manufacturing and construction industry. Second, the government should have addressed the expiring Bush tax cuts. Although I think the tax cuts in 2001 were not very effective in helping the economy recover from the recession back then and further worsened our government debt letting them expire at the end of 2010 will greatly hamper any recovery we maybe experiencing. Third, the stimulus package should have provided ample aid to states. Again multiplier estimates show unemployment compensation has one of the largest stimulus effects. Finally the stimulus package would have included money to help struggling homeowners. There are a large number of homeowners who did things right and have jobs, but find themselves underwater in their mortgage. Imagine buying a $300,000 home and putting $30,000 or $60,000 down to find yourself living in a home worth $150,000. You did nothing wrong, the government wanted everyone to be a homeowner and live the American Dream. Why are we punishing individuals that are doing it the right way? The government needed to help these homeowners restructure their loans which would have provided badly need stability to housing prices. In the end this bill would have cost significantly more, probably in the $1.5-2 trillion dollar range (nearly half would be from the extension of the tax cuts), but we would address a lot of future uncertainty back in 2009. As it stands we are left doing a patchwork of bills that will likely cost more than $2 trillion.

(One thing I didn't address was the tax credits for developing alternative energies. I think a more direct approach would be to tax dirty energies directly and let the market develop sustainable alternative energies. I will talk about this more in a later post.)

Now the government is wanting to pass another bill. Although this bill sounds like it has some good intentions, it is hard to say what the bill will look like after it goes through the political process. Additionally, we have to ask ourselves if we can afford another bill. Right now the patchwork process is not helping anyone, adding another $100 billion in spending will likely have little to no economic impact in the short run. At the same time I don't think we can afford a $1 trillion package that is similar in make up to the ARRA. This really puts the economy and politicians at a crossroads.

Sunday, September 5, 2010

Advice for Freshman and Sophomores

Here is an article by Greg Mankiw talking about what he views as the most important college classes. Mankiw is an Harvard economist and highly respected in the field.

I completely agree with his assessment. From my experience the most marketable students leaving college are those with a math/econ/finance background. This background prepares you for nearly any job in business (especially those interested in finance, investment banking, or economics), actuarial careers (what is an actuary), or graduate school (law, MBA, masters, or doctorate). For those not wanting an advanced degree economic majors do fair well in their careers (here is a link showing the highest paying majors and here's another).

At Gonzaga one could complete the bachelors of science in economics. This would entail 45 credit hours including both principles of micro and macro, intermediate macro, advanced micro, econometrics, economic thought, two additional econ electives, the calculus sequence, linear algebra, statistics, and one additional math or economics elective. At this point it makes sense to take two additional math courses (one 400 level), one class will count for the economics degree and the second course will complete the mathematics minor. In addition to the economics degree it is necessary to have a background in accounting and finance. You're in luck, you can combine the economics degree with a minor in analytical finance. To complete the analytical finance minor, one would need two classes in accounting and three classes in finance. In all, the analytical finance minor is 21 credit hours, but this includes principles of micro and macroeconomics. To put this in perspective those choosing to complete the finance concentration will only take five classes, but generally lack the background in mathematics.

Now can you complete these requirements within a four year period. You will need to complete 62 credits in the core for the University and College of Arts and Sciences. Fortunately, economics 201 and 202 will count for the six credits needed in social science and math 157 and 159 will count for the three credits needed in math for both cores. This reduces the core to 50 credit hours. The economics major is 45 hours, the mathematics minor is 6 additional hours, and the analytical finance minor adds 15 additional hours. In all, a bachelors of science in economics, minors in mathematics and analytical finance will take 66 hours. Including the additional 50 hours needed to satisfy core requirements means you will have completed 116 of the necessary 128 hours. Because your major is in the college of the arts and sciences, 104 of 128 hours for graduation need to be within the college. This is satisfied by taking one additional course within the college. Of the 116 hours taken to satisfy major, minor, and core requirements 101 credits will be taken in the college of arts and sciences. After taking one more course you are still left with 8 credit hours of your choosing. Here is where you can take activity courses or any other elective course. Additionally, you can spend a semester in Florence and still be able to complete the degree in four years!

I completely agree with his assessment. From my experience the most marketable students leaving college are those with a math/econ/finance background. This background prepares you for nearly any job in business (especially those interested in finance, investment banking, or economics), actuarial careers (what is an actuary), or graduate school (law, MBA, masters, or doctorate). For those not wanting an advanced degree economic majors do fair well in their careers (here is a link showing the highest paying majors and here's another).

At Gonzaga one could complete the bachelors of science in economics. This would entail 45 credit hours including both principles of micro and macro, intermediate macro, advanced micro, econometrics, economic thought, two additional econ electives, the calculus sequence, linear algebra, statistics, and one additional math or economics elective. At this point it makes sense to take two additional math courses (one 400 level), one class will count for the economics degree and the second course will complete the mathematics minor. In addition to the economics degree it is necessary to have a background in accounting and finance. You're in luck, you can combine the economics degree with a minor in analytical finance. To complete the analytical finance minor, one would need two classes in accounting and three classes in finance. In all, the analytical finance minor is 21 credit hours, but this includes principles of micro and macroeconomics. To put this in perspective those choosing to complete the finance concentration will only take five classes, but generally lack the background in mathematics.

Now can you complete these requirements within a four year period. You will need to complete 62 credits in the core for the University and College of Arts and Sciences. Fortunately, economics 201 and 202 will count for the six credits needed in social science and math 157 and 159 will count for the three credits needed in math for both cores. This reduces the core to 50 credit hours. The economics major is 45 hours, the mathematics minor is 6 additional hours, and the analytical finance minor adds 15 additional hours. In all, a bachelors of science in economics, minors in mathematics and analytical finance will take 66 hours. Including the additional 50 hours needed to satisfy core requirements means you will have completed 116 of the necessary 128 hours. Because your major is in the college of the arts and sciences, 104 of 128 hours for graduation need to be within the college. This is satisfied by taking one additional course within the college. Of the 116 hours taken to satisfy major, minor, and core requirements 101 credits will be taken in the college of arts and sciences. After taking one more course you are still left with 8 credit hours of your choosing. Here is where you can take activity courses or any other elective course. Additionally, you can spend a semester in Florence and still be able to complete the degree in four years!

Friday, September 3, 2010

Landon Christoper Herzog born 9/2/10

My son was born last night at 8:46pm. He weighed 6 pounds, 8 ounces. Conveniently, he was born on our third wedding anniversary. So far everyone is doing well, we will be leaving the hospital this afternoon and getting settled in at home. I hope everyone has a good weekend. Here are a couple pictures, he's been sleeping most of the time so I don't have many with his eye's open.

Thursday, September 2, 2010

Videos to Watch on the Financial Crisis

Here are a couple good videos that explain the financial crisis.

CNBC's House of Cards provides a very good introduction.

Frontline on PBS had two very good videos. Inside the Meltdown takes a look at beginning of the crisis starting with the collapse of Bear Stearns through collapses of AIG and Lehman Brothers. It is a little more technical. The Warning takes a closer look at the failure of Long Term Capital Management. Long Term Capital Management was the world's largest hedge fund that traded financial instruments similar to those that caused the financial crisis.

Finally, for those wondering more about Bernie Madoff here is a good video, The Madoff Affair.

These videos are for informational purposes. I get asked by a lot of students if there are any good websites or videos these are the best I have found.

CNBC's House of Cards provides a very good introduction.

Frontline on PBS had two very good videos. Inside the Meltdown takes a look at beginning of the crisis starting with the collapse of Bear Stearns through collapses of AIG and Lehman Brothers. It is a little more technical. The Warning takes a closer look at the failure of Long Term Capital Management. Long Term Capital Management was the world's largest hedge fund that traded financial instruments similar to those that caused the financial crisis.

Finally, for those wondering more about Bernie Madoff here is a good video, The Madoff Affair.

These videos are for informational purposes. I get asked by a lot of students if there are any good websites or videos these are the best I have found.

Why America Isn't Working

This is a great piece talking about why it takes so long to recover (you can read it here).

The honest answer – but one that few voters want to hear – is that there is no magic bullet. It took more than a decade to dig today’s hole, and climbing out of it will take a while, too. As Carmen Reinhart and I warned in our 2009 book on the 800-year history of financial crises (with the ironic title “This Time is Different”), slow, protracted recovery with sustained high unemployment is the norm in the aftermath of a deep financial crisis.He goes on to talk about why tax cuts and added government spending will not work. His conclusion is right on:

The bottom line is that Americans will have to be patient for many years as the financial sector regains its health and the economy climbs slowly out of its hole. The government can certainly help, but beware of pied pipers touting quick fixes.His book with Carmen Reinhart is a NY Times best seller. For those continuing in finance, economics, or accounting it is a must read.

Wednesday, September 1, 2010

Bank Capital Requirements

Here is a good article from the Economist supporting capital requirements:

Over the last three years there has been tremendous attention into financial reform. A major theme in our class will be discussing the role financial markets play in the economy and how to go about regulating these markets. Recently the US passed the Dodd-Frank bill which attempts to prevent future financial crises. Unfortunately, one area the bill fails to address is the need for bank capital requirements. Before getting into the gory details it may help to provide a brief side note on the role of bank capital.

Like any firm banks have assets and liabilities. Asset include loans made to households and business and government bonds. Liabilities include demand deposits (checking accounts) IRAs, and CDs, basically our accounts with banks. Bank capital is the difference between assets and liabilities. It shows up on the liabilities side of the balance sheet.

Banks prefer to not hold excess capital, they would prefer to pass the capital onto the owners in the form of equity or use the funds to create more loans. Nonetheless capital helps banks insurance against large loan losses. Remember loans (notably housing and commercial loans) appear on the asset side of the balance sheet, when banks experience large loan losses the asset side of the balance sheet decreases. If loan losses are large enough bank assets could become less than liabilities making the bank insolvent (i.e. the bank fails). Now because bank capital is a liability it helps offset loan losses.

Suppose you have two banks (A and B). Bank A has $100 million in capital and Bank B has $25 million. Each bank experiences large loan losses and writes down their assets by $50 million. Bank A will be left with $50 million in capital but Bank B will be insolvent with a net worth of -$25 million. If we go back 2 years, banks that failed lacked sufficient capital to insure against large loan losses.

Jump ahead to today and we still have not solved the bank capital requirements. Wall Street has argued against capital requirements, forcing banks into holding added capital will sufficiently hamper lending. I firmly believe we need to institution capital requirements based on three components:

1) The size of a bank's balance sheet. If mega banks pose added risk to the economy we need to force them into holding more capital.

2) The composition of a bank's assets. If banks want to hold riskier assets (i.e. subprime mortgages) we need to require greater capital requirements.

3) The composition of a bank's liabilities. If a bank has liquid liabilities (i.e. dependent on short-term financing) they are more prone to experience a bank run and a loss of funding, holding greater levels of capital will temper this threat.

The basis for my argument comes from the last 20 years of banking crises. We have seen large financial crises occur in Asian, Latin America, Scandinavia, and now the United States. In nearly every case banks did not hold sufficient amounts of capital. The solution to our financial crisis was to inject major banks with added capital (remember TARP). If banks were holding sufficient capital we could have prevented needing to bailout nearly every large bank.

Of course there was a fear of a large slowdown in global growth. Well, it turns out the costs of financial crises trumps the reduction in growth from a slowdown in banking lending. Banks would be forced into more due diligence when issuing loans and likely choose safer investments.

Two numbers stand out. First, the short-term cost of tougher rules is fairly low: assuming a three-percentage-point increase in capital ratios and a four-year implementation period, absolute GDP would be just 0.6% lower than it would otherwise have been. Second, and offsetting the first effect, once the new rules are in place the benefits from having fewer crises are big. In a base case and assuming a three-percentage-point capital-ratio increase, the absolute level of GDP rises by some 1.7%.

Over the last three years there has been tremendous attention into financial reform. A major theme in our class will be discussing the role financial markets play in the economy and how to go about regulating these markets. Recently the US passed the Dodd-Frank bill which attempts to prevent future financial crises. Unfortunately, one area the bill fails to address is the need for bank capital requirements. Before getting into the gory details it may help to provide a brief side note on the role of bank capital.

Like any firm banks have assets and liabilities. Asset include loans made to households and business and government bonds. Liabilities include demand deposits (checking accounts) IRAs, and CDs, basically our accounts with banks. Bank capital is the difference between assets and liabilities. It shows up on the liabilities side of the balance sheet.

Banks prefer to not hold excess capital, they would prefer to pass the capital onto the owners in the form of equity or use the funds to create more loans. Nonetheless capital helps banks insurance against large loan losses. Remember loans (notably housing and commercial loans) appear on the asset side of the balance sheet, when banks experience large loan losses the asset side of the balance sheet decreases. If loan losses are large enough bank assets could become less than liabilities making the bank insolvent (i.e. the bank fails). Now because bank capital is a liability it helps offset loan losses.

Suppose you have two banks (A and B). Bank A has $100 million in capital and Bank B has $25 million. Each bank experiences large loan losses and writes down their assets by $50 million. Bank A will be left with $50 million in capital but Bank B will be insolvent with a net worth of -$25 million. If we go back 2 years, banks that failed lacked sufficient capital to insure against large loan losses.

Jump ahead to today and we still have not solved the bank capital requirements. Wall Street has argued against capital requirements, forcing banks into holding added capital will sufficiently hamper lending. I firmly believe we need to institution capital requirements based on three components:

1) The size of a bank's balance sheet. If mega banks pose added risk to the economy we need to force them into holding more capital.

2) The composition of a bank's assets. If banks want to hold riskier assets (i.e. subprime mortgages) we need to require greater capital requirements.

3) The composition of a bank's liabilities. If a bank has liquid liabilities (i.e. dependent on short-term financing) they are more prone to experience a bank run and a loss of funding, holding greater levels of capital will temper this threat.

The basis for my argument comes from the last 20 years of banking crises. We have seen large financial crises occur in Asian, Latin America, Scandinavia, and now the United States. In nearly every case banks did not hold sufficient amounts of capital. The solution to our financial crisis was to inject major banks with added capital (remember TARP). If banks were holding sufficient capital we could have prevented needing to bailout nearly every large bank.

Of course there was a fear of a large slowdown in global growth. Well, it turns out the costs of financial crises trumps the reduction in growth from a slowdown in banking lending. Banks would be forced into more due diligence when issuing loans and likely choose safer investments.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)